A Snelson DataBase and Index

Includes the Snelson Coat of Arms & Armory

Person Page 788

|  |  |  |

Prisca (Brisque) Unknown1,2

F, #19677, Deceased, d. before 1018

Interactive Pedigree Button

Family: William V the Great Unknown (b. 969, d. 31 January 1030)

Main Events

| Also Known As | Prisca (Brisque) Unknown was also known as Prisca (Brisque) Unknown. |

| User Reference Number | She; 18888 |

| Marriage | Prisca (Brisque) Unknown and William V the Great Unknown were married in 1011.2,1 |

| Death | She died before 1018.2,1 |

| Her husband William V the Great Unknown died on 31 January 1030. |

Citations

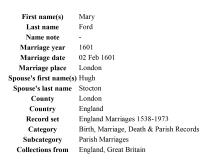

Mary Ford

F, #19683, Deceased, b. before 1580, d. 1 July 1640

Interactive Pedigree Button

Person Exhibits

Marriage Mary Ford & Hugh Stockton 1601

Parents

| Father | Richard Ford |

Family 1: Hugh Stockden (d. September 1603)

Family 2: Roger Snelson (b. about 1576, d. about October 1647)

Main Events

| Also Known As | Mary Ford was also known as Mary Snelson. |

| Also Known As | She was also known as Mary Stockden. |

| Also Known As | She was also known as Mary Stockton. |

| Biography | I think it highly probable that Mary Ford is the same person as Mary Stockden, as there are records as follows :- Hugh Stockden buried 8 Sep 1603 St James Garlickhithe (and the Parish Record MAY say that he was "a dier" ... I am not sure, but I think so. If anyone else can interpret the St. James, Garlickhithe record and writing, I would like to hear from you). She was then a widow ... and married Roger Snelson in 1604. I think that is what happened - subject to the Marriage to Roger NOT having her as a spinster. The parish records name her as "Mary Stockden". So, the only reference that Roger's wife was "Mary Ford" is on the Visitation of London. I just wonder whether Roger did not want to admit that his wife had been married previously ... who knows, but that would not surprise me. Although, I do not think that there was any stigma attached to such circumstances in those days - but Roger was an eccentrically proud man. |

| User Reference Number | She; 2333 |

| Birth | She was born before 1580 in Yarnfield, Somerset, Yarnfield tithing, a part of Maiden Bradley parish, on the north-west, and formerly in the county of Somerset. |

| Marriage | Mary Ford and Hugh Stockden were married on 2 February 1601 in St Thomas the Apostle, London.1 |

| Her husband Hugh Stockden died in September 1603. | |

| Marriage | Mary Ford and Roger Snelson were married on 11 January 1604 in the parish church, St. James', Garlickhithe, London, Boyd's Marriage Index has her name as Mary Stockton.2 |

| Death | She died on 1 July 1640 in London. |

| Burial | Mary's remains were buried on 2 July 1640 in St Mary, Islington, I am pretty sure that this is correct, as Roger refers in his Will of 1647 to his "late wife", so there is no doubt that Marir (Mary) died before him. [[Principal Role]] [[Witness Role: Buried]]. |

| Her husband Roger Snelson died about October 1647 in London. |

Citations

Charles Martel Unknown1,2

M, #19686, Deceased, b. 23 August 686, d. 22 October 741

Interactive Pedigree Button

Parents

| Father | Pippin of Herstal Unknown (b. about 640, d. 16 December 714) |

| Mother | Alpaida Unknown |

Family 1: Ruodhaid Unknown

Family 2: Swanahild Unknown

Family 3: Rotrude Unknown (b. 690, d. 724)

| Son | Carloman Unknown+ (b. about 710, d. 17 August 754) |

| Son | Pippin the Younger Unknown+ (b. 715, d. 24 September 768) |

| Daughter | Landrade Unknown+ (b. about 720) |

Main Events

| Marriage | Charles Martel Unknown and Ruodhaid Unknown were married Unknown GEDCOM info: Partner Unknown GEDCOM info: Mistress Unknown GEDCOM info: had children with Unknown GEDCOM info: Partner Unknown GEDCOM info: Mistress Unknown GEDCOM info: had children with.3,1 |

| Marriage | Charles Martel Unknown and Swanahild Unknown were married.3,1 |

| Marriage | Charles Martel Unknown and Rotrude Unknown were married.3,1 |

| Residence | He resided See notes.1 |

| User Reference Number | He; 18763 |

| Note | Event Memos from GEDCOM Import... Residence Charles Martel (or, in modern English, Charles the Hammer) (23 August 686 – 22 October 741) was the Mayor of the Palace and duke of the Franks. (Whatever the titles, he ruled the Frankish Realms.) He expanded his rule over all three of the Frankish kingdoms: Austrasia, Neustria and Burgundy. Martel was born in Herstal, in what is now Wallonia, Belgium, the illegitimate son of Pippin the Middle and his concubine Alpaida (or Chalpaida). He is best remembered for winning the Battle of Tours in 732, which has traditionally been characterized as an action saving Europe from the Muslim expansionism that had conquered Iberia. 'There were no further Muslim invasions of Frankish territory, and Charles's victory has often been regarded as decisive for world history, since it preserved western Europe from Muslim conquest and Islamization.' Though primarily remembered simply as the leader of the Christian army that prevailed at Tours, Charles Martel was a truly giant figure of the Dark Ages. A brilliant general in an age generally bereft of the same, he is considered the forefather of western heavy cavalry, chivalry, founder of the Carolingian Empire, (which was named after him), and a catalyst for the feudal system that would see Europe through the Dark Ages. (Although recent scholastic findings have suggested he was more of a beneficiary of the feudal system than a knowing agent for social change.) In December 714, Pippin the Middle died. He had, at his wife Plectrude's urging, designated Theudoald, his grandson by Plectrude's son Grimoald, his heir in the entire realm. This was immediately opposed by the nobles, for Theudoald was a child of eight years. Moving quickly, Plectrude seized Charles Martel, her husband's eldest surviving son, a bastard, and put him in prison in Cologne, the city which was destined to be her capital. This prevented an uprising on his behalf in Austrasia, but not in Neustria. In 715, the Neustrian noblesse proclaimed one Ragenfrid mayor of their palace on behalf of, and apparently with the support of, Dagobert III, the young king, who in fact had the legal authority to select a mayor, though by this time the Merovingian dynasty had lost most such regal powers. The Austrasians were not to be left supporting a woman and her young boy for long. Before the end of the year, Charles Martel had escaped from prison and been acclaimed mayor by the nobles of that kingdom. The Neustrians had been attacking Austrasia, and the nobles were waiting for a strong man to lead them against their invading countrymen. That year, Dagobert died and the Neustrians proclaimed Chilperic II king without the support of the rest of the Frankish people. In 716, Chilperic and Ragenfrid together led an army into Austrasia. The Neustrians allied with another invading force under Radbod, King of the Frisians, and met Charles in battle near Cologne, still held by Plectrude. Charles had little time to gather men, or prepare, and the result was the only defeat of his life. In fact, he fled the field as soon as he realized he did not have the time or the men to prevail, retreating to the mountains of the Eifel. The king and his mayor then turned to besiege their other rival in the city and took it and the treasury, and received the recognition of both Chilperic as king and Ragenfrid as mayor. Plectrude surrendered on Theudoald's behalf. At this juncture, events turned in favour of Charles. Having made the proper preparations, Charles fell upon the triumphant army near Malmedy as it was returning to its own province, and, in the ensuing Battle of Amblève, routed it and it fled. Several things were notable about this battle, in which Charles set the pattern for the remainder of his military career: First, he appeared where his enemies least expected him, while they were marching triumphantly home and far outnumbered him. He also attacked when least expected, at midday, when armies of that era traditionally were resting. Finally, he attacked them how they least expected it, by feigning a retreat to draw his opponents into a trap. The feigned retreat, next to unknown in Western Europe at that time—it was a traditionally eastern tactic—required both extraordinary discipline on the part of the troops and exact timing on the part of their commander. Charles, in this battle, had begun demonstrating the military genius that would mark his rule, in that he never attacked his enemies where, when, or how they expected, and the result was an unbroken victory streak that lasted until his death. In Spring 717, Charles returned to Neustria with an army and confirmed his supremacy with a victory at Vincy, near Cambrai. He chased the fleeing king and mayor to Paris before turning back to deal with Plectrude and Cologne. He took the city and dispersed her adherents. He allowed both Plectrude and Theudoald to live, and treated them with kindness—unusual for those Dark Ages, when mercy to a former jailer, or a potential rival, was rare. On this success, he proclaimed one Clotaire IV king of Austrasia in opposition to Chilperic and deposed the archbishop of Rheims, Rigobert, replacing him with one Milo, a lifelong supporter. After subjugating all Austrasia, he marched against Radbod and pushed him back into his territory, even forcing the concession of West Frisia (later Holland). He also sent the Saxons back over the Weser and thus secured his borders—in the name of the new king, of course. More than any other prior mayor of the palace, however, absolute power lay with Charles. Though he never cared about titles, his son Pippin did, and finally asked the Pope 'who should be King, he who has the title, or he who has the power?' The Pope, highly dependent on Frankish armies for his independence from Lombard and Byzantine power (the Byzantine emperor still considered himself to be the only legitimate 'Roman' Emperor, and thus, ruler of all of the provinces of the ancient empire, whether recognised or not), declared for 'he who had the power' and immediately crowned Pippin. Decades later, in 800, Pippin's son Charlemagne was crowned emperor by the Pope, further extending the 'he who had the power' principle by delegitimising the nominal authority of the Byzantine emperor in the Italian peninsula (which had, by then, shrunk to little more than Apulia and Calabria at best) and ancient Roman Gaul, including the Iberian outposts Charlmagne had established in the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees, what today forms Catalonia. In short, though the Byzantine Emperor claimed authority over all the old Roman Empire, as the legitimate 'Roman' Emperor, and this may have been legally true, it was simply not reality. The bulk of the Western Roman Empire had come under Carolingian rule, the Byzantine Emperor having had almost no authority in the West since the sixth century, though Charlemagne, a consummate politician, preferred to avoid an open breach with Constantinople. What was occurring was the birth of an institution unique in history: the Holy Roman Empire. Though the sardonic Voltaire ridiculed its nomenclature, saying that the Holy Roman Empire was 'neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire,' it constitued an enormous political power for a time, especially under the Saxon and Salian dynasties and, to a lesser, extent, the Hohenstaufen. It lasted until 1806, by then a nonentity. Though his grandson became its first emperor, the 'empire' such as it was, was largely born during the reign of Charles Martel. In 718, Chilperic responded to Charles' new ascendancy by making an alliance with Odo the Great (or Eudes, as he is sometimes known), the duke of Aquitaine, who had made himself independent during the civil war in 715, but was again defeated, at Soissons, by Charles. The king fled with his ducal ally to the land south of the Loire and Ragenfrid fled to Angers. Soon Clotaire IV died and Odo gave up on Chilperic and, in exchange for recognising his dukeship, surrendered the king to Charles, who recognised his kingship over all the Franks in return for legitimate royal affirmation of his mayoralty, likewise over all the kingdoms (718). The ensuing years were full of strife. Between 718 and 723, Charles secured his power through a series of victories: he won the loyalty of several important bishops and abbots (by donating lands and money for the foundation of abbeys such as Echternach, he subjugated Bavaria and Alemannia, and he defeated the pagan Saxons. Having unified the Franks under his banner, Charles was determined to punish the Saxons who had invaded Austrasia. Therefore, late in 718, he laid waste their country to the banks of the Weser, the Lippe, and the Ruhr. He defeated them in the Teutoburg Forest, where no outside power since the legions of Varus had ventured and where, unlike Rome, he defeated the inhabitants with ease. In 719, Charles seized West Frisia without any great resistance on the part of the Frisians, who had been subjects of the Franks but had seized control upon the death of Pippin. Although Charles did not trust the pagans, their ruler, Aldegisel, accepted Christianity, and Charles sent Willibrord, bishop of Utrecht, the famous 'Apostle to the Frisians' to convert the people. Charles also did much to support Winfrid, later Saint Boniface, the 'Apostle of the Germans.' When Chilperic II died the following year (720), Charles appointed as his successor the son of Dagobert III, Theuderic IV, who was still a minor, and who occupied the throne from 720 to 737. Charles was now appointing the kings whom he supposedly served, rois fainéants who were mere puppets in his hands; by the end of his reign they were so useless that he didn't even bother appointing one. At this time, Charles again marched against the Saxons. Then the Neustrians rebelled under Ragenfrid, who had been left the county of Anjou. They were easily defeated (724), but Ragenfrid gave up his sons as hostages in turn for keeping his county. This ended the civil wars of Charles' reign. The next six years were devoted in their entirety to assuring Frankish authority over the dependent Germanic tribes. Between 720 and 723, Charles was fighting in Bavaria, where the Agilolfing dukes had gradually evolved into independent rulers, recently in alliance with Liutprand the Lombard. He forced the Alemanni to accompany him, and Duke Hugbert submitted to Frankish suzerainty. In 725 and 728, he again entered Bavaria and the ties of lordship seemed strong. From his first campaign, he brought back the Agilolfing princess Swanachild, who apparently became his concubine. In 730, he marched against Lantfrid, duke of Alemannia, who had also become independent, and killed him in battle. He forced the Alemanni capitulation to Frankish suzerainty and did not appoint a successor to Lantfrid. Thus, southern Germany once more became part of the Frankish kingdom, as had northern Germany during the first years of the reign. But by 730, his own realm secure, Charles began to prepare exclusively for the coming storm from the west. In 721, the emir of Córdoba had built up a strong army from Morocco, Yemen, and Syria to conquer Aquitaine, the large duchy in the southwest of Gaul, nominally under Frankish sovereignty, but in practice almost independent in the hands of the Odo the Great since the Merovingian kings had lost power. The invading Muslims besieged the city of Toulouse, then Aquitaine's most important city, and Odo immediately left to find help. He returned three months later just before the city was about to surrender and defeated the Muslim invaders on June 9, 721, at what is now known as the Battle of Toulouse. The defeat was essentially the result of a classic enveloping movement on Odo's part. After Odo originally fled, the Muslims became overconfident and, instead of maintaining strong outer defenses around their siege camp and continuing scouting, did neither. Thus, when Odo returned, he was able to launch a near complete surprise attack on the besieging force, scattering it at the first attack, and slaughtering units which were resting, or who fled without weapons or armour. Charles had watched the Iberian situation since Toulouse, convinced the Muslims would return, and while he was securing his own realms, he was also preparing for war against the Umayyads. He believed he needed a virtually fulltime army, one he could train, as a core of veterans to add to the usual conscripts the Franks called up in time of war. During the Early Middle Ages, troops were only available after the crops had been planted and before harvesting time. To train the kind of infantry which could withstand the Muslim heavy cavalry, Charles needed them year-round, and he needed to pay them so their families could buy the food they would have otherwise grown. To obtain this money, he seized church lands and property, and used the funds to pay his soldiers. The same Charles who had secured the support of the ecclesia by donating land, seized some of it back between 724 and 732. The Church was enraged, and, for a time, it looked as though Charles might even be excommunicated for his actions. But then came a significant invasion. It has been noted that Charles Martel could have pursued the wars against the Saxons—but he was determined to prepare for what he thought was a greater danger. Instead of concentrating on conquest to his east, he prepared for the storm gathering in the west. Well aware of the danger posed by the Muslims after the Battle of Toulouse, in 721, it has been explained that he used the intervening years to consolidate his power, and gather and train the core of a veteran army that would stand ready to defend Christianity itself (at Tours). It is also vital to note that the Muslims were not aware, at that time, of the true strength of the Franks, or the fact that they were building a real army, not the typical barbarian hordes which had infested Europe after Rome's fall. They considered the Germanic tribes, including the Franks, simply barbarians and were not particularly concerned about them. (The Arab Chronicles, the history of that age, show that awareness of the Franks as a growing military power came only after the Battle of Tours when the Caliph expressed shock at his army's catastrophic defeat). Further, the Muslims had not bothered with the normal scouting of potential foes, for if they had, they surely would have noted Charles Martel as a force to be reckoned with in his own account. Martel's thorough domination of Europe from 717 on, and his sound defeat of all powers who contested his dominion, should have alerted the Moors that, not only was a real power rising in the ashes of the Western Roman Empire, but a truly gifted general was leading it. Thus, when they launched their great invasion of 732, they were not prepared to confront Martel and his Frankish army. This, in retrospect, was a disastrous mistake. Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi was a good general and should have done two things he neglected to do: he failed to assess the strength of the Franks in advance of invasion, assuming that they would not come to the aid of their Aquitanian cousins; and he failed to scout the movements of the Frankish army and Charles Martel. Had he done either, he would have curtailed his lighthorse ravaging throughout lower Gaul and marched at once, with his full power, against the Franks. This strategy would have nullified every advantage Charles had at Tours, as the invaders would have not been burdened with booty that played such a huge role in the battle. They would not have lost a single warrior in the battles they fought prior to Tours. (Although they lost relatively few men subduing Aquitane, the casualties they did suffer may have been significant at Tours). Finally, the Moors would have bypassed weaker opponents such as Odo, whom they could have picked off at will later, while moving at once to force battle with the real power in Europe, and at least partially picked the battlefield. While some military historians point out that leaving enemies in your rear is generally unwise, the Mongols proved that indirect attack and bypassing weaker foes to eliminate the strongest first is a devastatingly effective mode of invasion. In this case, those enemies posed virtually no danger, given the ease with which the Muslims destroyed them. The real danger was Charles, and the failure to scout Europe adequately proved disastrous. Had Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi realized how thoroughly Martel had dominated Europe for 15 years, and how gifted a commander he was, he would not have allowed Charles Martel to pick the time and place the two powers would collide, which historians agree was pivotal to his victory. The Cordoban emirate had previously invaded Gaul and had been stopped in its northward sweep at the Battle of Toulouse, in 721. The hero of that less celebrated event had been Odo the Great, Duke of Aquitaine, who was not the progenitor of a race of kings and patron of chroniclers. It has previously been explained how Odo defeated the invading Muslims, but when they returned, things were far different. The arrival in the interim of a new emir of Cordoba, Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, who brought with him a huge force of Arabs and Berber horsemen, triggered a far greater invasion. Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi had been at Toulouse, and the Arab Chronicles make clear he had strongly opposed the Emir's decision not to secure outer defenses against a relief force, which allowed Odo and his infantry to attack with impunity before the Islamic cavalry could assemble or mount. Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi had no intention of permitting such a disaster again. This time the Muslim horsemen were ready for battle, and the results were horrific for the Aquintanians. Odo, hero of Toulouse, was badly defeated in the Muslim invasion of 732 at the Battle of the River Garonne —where the western chroniclers state, 'God alone knows the number of the slain'— and the city of Bordeaux was sacked and looted. Odo fled to Charles, seeking help. Charles agreed to come to Odo's rescue, provided Odo acknowledged Charles and his house as his Overlords, which Odo did formally at once. Thus, Odo faded into history while Charles marched into it. Charles was pragmatic; his former enemy Odo and his Aquitanian nobles formed the right flank of Charles' forces at Tours. The Battle of Tours earned Charles the cognomen 'Martel', for the merciless way he hammered his enemies. Many historians, including the great military historian Sir Edward Creasy, believe that had he failed at Tours, Islam would probably have overrun Gaul , and perhaps the remainder of western Christian Europe. Gibbon made clear his belief that the Muslims would have conquered from Rome to the Rhine, and even England, with ease, had Martel not prevailed. Creasy said 'the great victory won by Charles Martel ... gave a decisive check to the career of Arab conquest in Western Europe, rescued Christendom from Islam, [and] preserved the relics of ancient and the germs of modern civilization.' Gibbon's belief that the fate of Christianity hinged on this battle is echoed by other historians including William E. Watson, and was very popular for most of modern historiography. It fell somewhat out of style in the twentieth century, when historians such as Bernard Lewis contended that Arabs had little intention of occupying northern France. More recently, however, many historians have tended once again to view the Battle of Tours as a very significant event in the history of Europe and Christianity. The Battle of Tours probably took place somewhere between Tours and Poitiers (hence its other name: Battle of Poitiers). The Frankish army, under Charles Martel, consisted mostly of veteran infantry, somewhere between 15,000 and 75,000 men. While Charles had some cavalry, they did not have stirrups, so he had them dismount and reinforce his phalanx. Odo and his Aquitanian nobility were also normally cavalry, but they also dismounted at the Battle's onset, to buttress the phalanx. Responding to the Muslim invasion, the Franks had avoided the old Roman roads, hoping to take the invaders by surprise. Martel believed it was absolutely essential that he not only take the Muslims by surprise, but that he be allowed to select the ground on which the battle would be fought, ideally a high, wooded plain where the Islamic horsemen, already tired from carrying armour, would be further exhausted charging uphill. Further, the woods would aid the Franks in their defensive square by partially impeding the ability of the Muslim horsemen to make a clear charge. From the Muslim accounts of the battle, they were indeed taken by surprise to find a large force opposing their expected sack of Tours, and they waited for six days, scouting the enemy and summoning all their raiding parties so their full strength was present for the battle. Emir Abdul Rahman was an able general who did not like the unknown at all, and he did not like charging uphill against an unknown number of foes who seemed well-disciplined and well-disposed for battle. But the weather was also a factor. The Germanic Franks, in their wolf and bear pelts, were more used to the cold, better dressed for it, and despite not having tents, which the Muslims did, were prepared to wait as long as needed, the fall only growing colder. On the seventh day, the Muslim army, mostly Berber and Arab horsemen and led by Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, attacked. During the battle, the Franks defeated the Islamic army and the emir was killed. While Western accounts are sketchy, Arab accounts are fairly detailed in describing how the Franks formed a large square and fought a brilliant defensive battle. Rahman had doubts before the battle that his men were ready for such a struggle, and should have had them abandon the loot which hindered them, but instead decided to trust his horsemen, who had never failed him. Indeed, it was thought impossible for infantry of that age to withstand armoured cavalry. Martel managed to inspire his men to stand firm against a force which must have seemed invincible to them, huge mailed horsemen, who, in addition, probably vastly outnumbered the Franks. In one of the rare instances where medieval infantry stood up against cavalry charges, the disciplined Frankish soldiers withstood the assaults even though, according to Arab sources, the Arab cavalry several times broke into the interior of the Frankish square. Both accounts agree that the Muslims had broken into the square and were trying to kill Martel, whose liege men had surrounded him and would not be broken, when a trick Charles had planned before the battle bore fruit beyond his wildest dreams. Both Western and Muslim accounts of the battle agree that sometime during the height of the fighting, with the battle still in grave doubt, scouts sent by Martel to the Muslim camp began freeing prisoners. Fearing loss of their plunder, a large portion of the Muslim army abandoned the battle and returned to camp to protect their spoils. In attempting to stop what appeared to be a retreat, Abdul Rahman was surrounded and killed by the Franks, and what started as a ruse ended up a real retreat, as the Muslim army fled the field that day. The Franks resumed their phalanx, and rested in place through the night, believing the battle would resume at dawn of the following morning. The next day, when the Muslims did not renew the battle, the Franks feared an ambush. Charles at first believed the Muslims were attempting to lure him down the hill and into the open, a tactic he would resist at all costs. Only after extensive reconnaissance by Frankish soldiers of the Muslim camp—which by both accounts had been so hastily abandoned that even the tents remained, as the Muslim forces headed back to Iberia with what spoils remained that they could carry—was it discovered that the Muslims had retreated during the night. As the Arab Chronicles would later reveal, the generals from the different parts of the Caliphate, Berbers, Arabs, Persians and many more, had been unable to agree on a leader to take Abd er Rahman's place as Emir, or even to agree on a commander to lead them the following day. Only the Emir, Abd er Rahman, had a Fatwa from the Caliph, and thus absolute authority over the faithful under arms. With his death, and with the varied nationalities and ethnicities present in an army drawn from all over the Caliphate, politics, racial and ethnic bias, and personalities reared their head. The inability of the bickering generals to select anyone to lead resulted in the wholesale withdrawal of an army that might have been able to resume the battle and defeat the Franks. In the subsequent decade, Charles led the Frankish army against the eastern duchies, Bavaria and Alemannia, and the southern duchies, Aquitaine and Provence. He dealt with the ongoing conflict with the Frisians and Saxons to his northeast with some success, but full conquest of the Saxons and their incorporation into the Frankish empire would wait for his grandson Charlemagne, primarily because Martel concentrated the bulk of his efforts against Muslim expansion. So instead of concentrating on conquest to his east, he continued expanding Frankish authority in the west, and denying the Emirite of Córdoba a foothold in Europe. After his victory at Tours, Martel continued on in campaigns in 736 and 737 to drive other Muslim armies from bases in Gaul after they again attempted to get a foothold in Europe beyond al-Andalus. Between his victory of 732 and 735, Charles reorganized the kingdom of Burgundy, replacing the counts and dukes with his loyal supporters, thus strengthening his hold on power. He was forced, by the ventures of Radbod, duke of the Frisians (719-734), son of the Duke Aldegisel who had accepted the missionaries Willibrord and Boniface, to invade independence-minded Frisia again in 734. In that year, he slew the duke, who had expelled the Christian missionaries, in battle and so wholly subjugated the populace (he destroyed every pagan shrine) that the people were peaceful for twenty years after. The dynamic changed in 735 because of the death of Odo the Great, who had been forced to acknowledge, albeit reservedly, the suzerainty of Charles in 719. Though Charles wished to unite the duchy directly to himself and went there to elicit the proper homage of the Aquitainians, the nobility proclaimed Odo's son, Hunold, whose dukeship Charles recognised when the Arabs invaded Provence the next year, and who equally was forced to acknowledge Charles as overlord as he had no hope of holding off the Muslims alone. This naval Arab invasion was headed by Abdul Rahman's son. It landed in Narbonne in 736 and moved at once to reinforce Arles and move inland. Charles temporarily put the conflict with Hunold on hold, and descended on the Provençal strongholds of the Muslims. In 736, he retook Montfrin and Avignon, and Arles and Aix-en-Provence with the help of Liutprand, King of the Lombards. Nîmes, Agde, and Béziers, held by Islam since 725, fell to him and their fortresses were destroyed. He crushed one Muslim army at Arles, as that force sallied out of the city, and then took the city itself by a direct and brutal frontal attack, and burned it to the ground to prevent its use again as a stronghold for Muslim expansion. He then moved swiftly and defeated a mighty host outside of Narbonnea at the River Berre, but failed to take the city. Military historians believe he could have taken it, had he chosen to tie up all his resources to do so—but he believed his life was coming to a close, and he had much work to do to prepare for his sons to take control of the Frankish realm. A direct frontal assault, such as took Arles, using rope ladders and rams, plus a few catapults, simply was not sufficient to take Narbonne without horrific loss of life for the Franks, troops Martel felt he could not lose. Nor could he spare years to starve the city into submission, years he needed to set up the administration of an empire his heirs would reign over. He left Narbonne therefore, isolated and surrounded, and his son would return to liberate it for Christianity. Provence, however, he successfully rid of its foreign occupiers, and crushed all foreign armies able to advance Islam further. Notable about these campaigns was Charles' incorporation, for the first time, of heavy cavalry with stirrups to augment his phalanx. His ability to coordinate infantry and cavalry veterans was unequaled in that era and enabled him to face superior numbers of invaders, and to decisively defeat them again and again. Some historians believe the Battle against the main Muslim force at the River Berre, near Narbonne, in particular was as important a victory for Christian Europe as Tours. In Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels, Antonio Santosuosso, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Western Ontario, and considered an expert historian in the era in dispute, puts forth an interesting modern opinion on Martel, Tours, and the subsequent campaigns against Rahman's son in 736-737. Santosuosso presents a compelling case that these later defeats of invading Muslim armies were at least as important as Tours in their defence of Western Christendom and the preservation of Western monasticism, the monasteries of which were the centers of learning which ultimately led Europe out of her Dark Ages. He also makes a compelling argument, after studying the Arab histories of the period, that these were clearly armies of invasion, sent by the Caliph not just to avenge Tours, but to begin the conquest of Christian Europe and bring it into the Caliphate. Further, unlike his father at Tours, Rahman's son in 736-737 knew that the Franks were a real power, and that Martel personally was a force to be reckoned with. He had no intention of allowing Martel to catch him unawares and dictate the time and place of battle, as his father had, and concentrated instead on seizing a substantial portion of the coastal plains around Narbonne in 736 and heavily reinforced Arles as he advanced inland. They planned from there to move from city to city, fortifying as they went, and if Martel wished to stop them from making a permanent enclave for expansion of the Caliphate, he would have to come to them, in the open, where, he, unlike his father, would dictate the place of battle. All worked as he had planned, until Martel arrived, albeit more swiftly than the Moors believed he could call up his entire army. Unfortunately for Rahman's son, however, he had overestimated the time it would take Martel to develop heavy cavalry equal to that of the Muslims. The Caliphate believed it would take a generation, but Martel managed it in five short years. Prepared to face the Frankish phalanx, the Muslims were totally unprepared to face a mixed force of heavy cavalry and infantry in a phalanx. Thus, Charles again championed Christianity and halted Muslim expansion into Europe, as the window was closing on Islamic ability to do so. These defeats were the last great attempt at expansion by the Umayyad Caliphate before the destruction of the dynasty at the Battle of the Zab, and the rending of the Caliphate forever, especially the utter destruction of the Muslim army at River Berre near Narbonne in 737. In 737, at the tail end of his campaigning in Provence and Septimania, the king, Theuderic IV, died. Martel, titling himself maior domus and princeps et dux Francorum, did not appoint a new king and nobody acclaimed one. The throne lay vacant until Martel's death. As the historian Charles Oman says, 'he cared not for name or style so long as the real power was in his hands.' The interregnum, the final four years of Charles' life, was more peaceful than most of it had been and much of his time was now spent on administrative and organisational plans to create a more efficient state. Though, in 738, he compelled the Saxons of Westphalia to do him homage and pay tribute, and in 739 checked an uprising in Provence, the rebels being under the leadership of Maurontus. Charles set about integrating the outlying realms of his empire into the Frankish church. He erected four dioceses in Bavaria (Salzburg, Regensburg, Freising, and Passau) and gave them Boniface as archbishop and metropolitan over all Germany east of the Rhine, with his seat at Mainz. Boniface had been under his protection from 723 on; indeed the saint himself explained to his old friend, Daniel of Winchester, that without it he could neither administer his church, defend his clergy, nor prevent idolatry. It was Saint Boniface who had defended Charles most stoutly for his deeds in seizing ecclesiastical lands to pay his army in the days leading to Tours, as one doing what he must to defend Christianity. In 739, Pope Gregory III begged Charles for his aid against Liutprand, but Charles was loathe to fight his onetime ally and ignored the Papal plea. Nonetheless, the Papal applications for Frankish protection showed how far Martel had come from the days he was tottering on excommunication, and set the stage for his son and grandson to literally rearrange Italy to suit the Papacy, and protect it. Charles Martel died on October 22, 741, at Quierzy-sur-Oise in what is today the Aisne département in the Picardy region of France. He was buried at Saint Denis Basilica in Paris. His territories were divided among his adult sons a year earlier: to Carloman he gave Austrasia and Alemannia (with Bavaria as a vassal), to Pippin the Younger Neustria and Burgundy (with Aquitaine as a vassal), and to Grifo nothing, though some sources indicate he intended to give him a strip of land between Neustria and Austrasia. Although it took another two generations for the Franks to drive all the Arab garrisons out of Septimania and across the Pyrenees, Charles Martel's halt of the invasion of French soil turned the tide of Islamic advances, and the unification of the Frankish kingdoms under Martel, his son Pippin the Younger, and his grandson Charlemagne created a western power which prevented the Emirate of Córdoba from expanding over the Pyrenees. Martel, who in 732 was on the verge of excommunication, instead was recognised by the Church as its paramount defender. Pope Gregory II wrote him more than once, asking his protection and aid, and he remained, till his death, fixated on stopping the Muslims. Martel's son Pippin the Younger kept his father's promise and returned and took Narbonne by siege in 759, and his grandson, Charlemagne, actually established the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees in part of what today is Catalonia, reconquering Girona in 785 and Barcelona in 801. This sector of what is now Spain was then called 'The Moorish Marches' by the Carolingians, who saw it as not just a check on the Muslims in Hispania, but the beginning of taking the entire country back. Charles Martel married twice: Rotrude (690 -724), with children: * Hiltrude (d. 754), married Odilo I, Duke of Bavaria * Carloman * Landres, married Sigrand, Count of Hesbania * Auda, Aldana, or Alane, married Thierry IV, Count of Autun and Toulouse * Pippin the Younger Swanhild with child: * Grifo Charles Martel also had a mistress, Ruodhaid: * Bernard (b. before 732-787) * Hieronymus * Remigius (d. 771.) |

| Birth Reg | He; Rotrude Unknown; 2nd cousins 1 removed1 |

| His wife Ruodhaid Unknown died. | |

| His wife Swanahild Unknown died. | |

| Birth | He was born on 23 August 686.2,1 |

| His son Carloman Unknown was born about 710. | |

| His father Pippin of Herstal Unknown died on 16 December 714. | |

| His son Pippin the Younger Unknown was born in 715. | |

| His daughter Landrade Unknown was born about 720. | |

| His wife Rotrude Unknown died in 724. | |

| Death | Charles Martel Unknown died on 22 October 741, at age 55.2,1 |

Citations

Michel Edouard de la Tour Willems

M, #19687, Deceased, b. 1 July 1939, d. 16 November 2009

| Consanguinity | 3rd cousin of Adrian John Snelson |

Parents

| Father | Vincent Jacques Willems (b. 1909, d. 10 February 1983) |

| Mother | Winifred Mary English (b. 14 August 1909, d. 14 December 1944) |

| Person References | Brigid Troy bef 1830 Johannes English 1815 - 1867 |

Main Events

| User Reference Number | Michel Edouard de la Tour Willems; 23899 |

| Birth | He was born on 1 July 1939 in Georgetown, Demarara, Guyana, was born <()> <()>. |

| His mother Winifred Mary English died on 14 December 1944 in Minnesota, USA. | |

| Residence | He resided in Twickenham Green, Twickenham, Middlesex, in 1968 Address: 5 Ellerman Avenue. |

| His father Vincent Jacques Willems died on 10 February 1983 in Hastings, Christ Church, Barbados. | |

| Death | Michel Edouard de la Tour Willems died on 16 November 2009, at age 70, in Authon, Eure-et-Loir, France. |

Parvie Unknown1

F, #19695, Deceased

Interactive Pedigree Button

Family: Otto Unknown (d. 25 May 1045)

| Son | Herbert IV Unknown+ (d. about 1080) |

Main Events

| Also Known As | Parvie Unknown was also known as Parvie Unknown. |

| Birth | She was born Person Source, Y.2 |

| Death | She died Y Y, Y.1 |

| User Reference Number | She; 18638 |

| Birth | She was born about 990.1 |

| Marriage | Parvie Unknown and Otto Unknown were married about 1030.1 |

| Her husband Otto Unknown died on 25 May 1045. |

Citations

Maura Crowe

F, #19696, Deceased, b. 1960, d. 1960

| Consanguinity | 3rd cousin of Adrian John Snelson |

Parents

| Father | John Desmond Crowe (b. 29 September 1926, d. February 1990) |

| Mother | Joan Barbara Mack (b. 19 April 1931, d. 2005) |

| Person References | Brigid Troy bef 1830 Johannes English 1815 - 1867 |

Main Events

| User Reference Number | Maura Crowe; 23766 |

| Birth | She was born in 1960. |

| Death | She died in 1960, at age ~0. |

| Her father John Desmond Crowe died in February 1990 in Trafford, Manchester, England. | |

| Her mother Joan Barbara Mack died in 2005. |